The auteur notion that cinema has long embraced celebrates filmmakers whose body of work exudes a distinctive voice, offering audiences a peek into the mind of such visionaries. More often than not, the film surpasses mere entertainment bringing its audiences into a state of reflection and encouraging them to question the film’s significance beyond its frame.

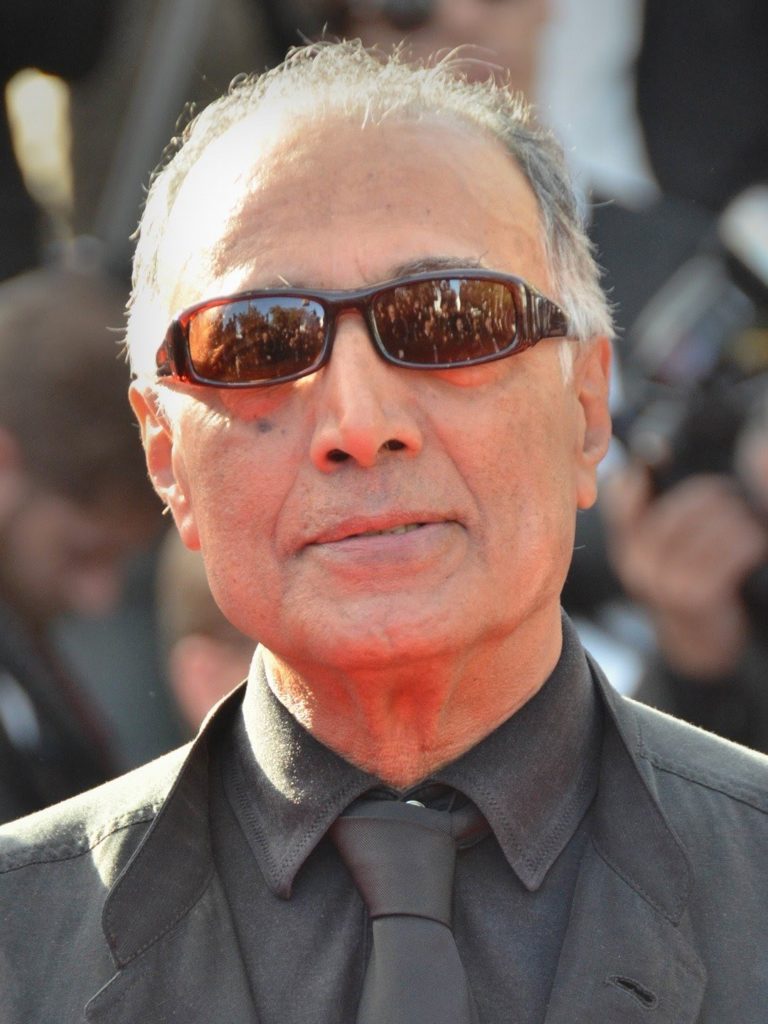

Among the many auteurs of cinema is an Iranian filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami. To fully understand Kiarostami’s works and its merits, it is important to consider his background as an artist and his roots as a filmmaker. Kiarostami was born in Tehran on the 22nd of June 1940. His father was a painter and decorator and aptly his first foray into the arts came in the form of painting which he pursued at Tehran University School of Fine Arts. Much of Kiarostami’s films feature stunning visual landscapes and interesting compositions, qualities brought forward from his visual art background and his time as an artist, Kiarostami was also heavily influenced by Iranian poetry. Kiarostami only began making films in 1969 when he started a filmmaking department at Kanoon, the institute for the intellectual development of children and young adults. There, he honed his craft in filmmaking which will later contribute significantly to the Iranian New Wave.

Don’t Miss: Portrait of a Lady on Fire: What It Means To Truly See

The Iranian New Wave began in 1969 with the Darius Mehrjui’s film, The Cow, along with directors such as Forough Farrokhzad, Jafar Panahi, and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Kiarostami was instrumental in driving the Iranian New Wave forward which produced 40 to 50 films in a span of 3 to 4 years. The Iranian new wave is frequently compared to Italian neo-realism as they both depict the realities of the ordinary men in the natural environments with narratives rooted in everyday life thus these films are often rich in cultural value. Because of its nature, the film movement is also credited for blurring the lines between fiction and nonfiction, applying elements of documentary filmmaking into its narrative films.

Considering the political landscape of Iran, the efforts of the Iranian wave and its directors are commendable. Iranian cinema faces much pressure from the government with strict censorship over many of the films produced in Iran. In the fundamentalist Muslim nation, the government rigorously controls much of the media which is largely centered on propaganda. After the Iranian revolution in 1979, many of Iran’s filmmakers fled the country to seek greener pastures, Kiarostami, however, stayed on.

Interesting: The Tree of Life: A Non-Spoiler Review

Kiarostami’s time at Kanoon from 1969 to 1985 was an important phase in his film career as it provided him the most favorable environment in Iran for any Iranian filmmaker. Kanoon faced little financial restrictions or interference from authorities allowing Kiarostami the freedom to experiment and better himself as a filmmaker. It was here that his film style began to develop as he set about exploring themes in line with the center’s agenda of educating children. Kiarostami’s first film, Bread and Alley, tells the story of a young boy who stumbles across an aggressive dog on his way home and in, Two Solution for One Problem, Kiarostami presents the story of 2 boys and how they resolve the conflicts with childlike simplicity.

While his later films would evolve to explore heavier themes such as ethics, self-identity, life, and death, the minimalistic approach to filmmaking would remain. Children also continued to be a key subject in many of Kiarostami’s later films often placing them opposite adult characters to establish interesting relationships, encouraging questions of morality by juxtaposing the innocence of childhood with the experience of an adult. While most would avoid the difficulty of directing children, Kiarostami takes it a step further with this preference for casting non-actors in his films and it is the consistency and authenticity of the performances that emphasize Kiarostami’s mastery of directing. Kiarostami also often shoots entire scenes in cars taking advantage of the scenic landscapes of rural Iran offers. He allows his characters to endlessly meander picturesque deserts and hills, a beautiful metaphor for the journey of life prevalent in many of his films. Another feature of Kiarostami’s films is his unique characters. From an imposter pretending to be a film director to a man looking to be buried, Kiarostami offers in his films a range of characters worth pondering over.

Worth Reading: An Ode To Leonard Cohen

While the Iranian New Wave is known for challenging the notions of fiction and reality, the films of Kiarostami, many of which are self-reflexive, further obscures the difference with the documentary-like performances of his actors, his choice of visual landscapes, and his naturalistic cinematography, Kiarostami truly pushes the boundaries and no other film better exemplifies this than his 1990’s film, Close-Up.

Close-Up tells the true story of Hossain Sabzian who impersonated Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf and cheated the Ahankhah family into thinking that they would be acting for his next film. Kiarostami adopted a truly bizarre approach in shooting Close-Up, gathering the actual people involved in the real life-case, from Hossain Sabzian to the Ahankhah family and the judge who passed the verdict to reenact the entire saga acting as themselves under his direction. Often he would interject from off-screen with questions directed by the actors themselves. The film blends actual documentary footage such as video interviews with the persons involved as well as footage from the trial, the scenes reenacted by Sabzian and the Ahankhah family, therefore, making it a challenge to differentiate between what was staged and what actually happened. Close-Up showcases Kiarostami’s method of simple and direct filmmaking. In terms of cinematography, he often employs long-take close-ups to allow his characters to deliver dialogue. These shots are often static, with camera movement motivated only by the actions of characters.

The use of sound in Kiarostami’s films is also important, not in the way sound effects are important to the blockbusters of Hollywood, but in how they create the off-screen space. Kiarostami often fills to communicate to the audience the wall beyond the frame. In The Wind Will Carry Us, a film crew under the guise of production engineers arrives in a village to await the death of an old woman in order to document the moaning rituals of the locals. In the film, Kiarostami often interjects long takes with actors communicating with people off-screen, the effect is a heightened sense of realism where performing for the audience is less of a priority than the character’s ultimate purpose. In doing so, Kiarostami extends the world of the film outside of what is seen on screen effectively including the audience in the film. Well, participation is one of an observer as such the deceptively simple cinematography has, in fact, a calculated intention to serve as a unique first-person perspective for the viewer.

The Wind Will Carry Us also features the landscapes of rural Iran often seen in Kiarostami’s films. The Mise-en-scene is largely unaltered with all of the scenes shot on location with available light. As with all of Kiarostami’s films, he opts for naturalistic performances from his actors. These elements combined help to achieve Kiarostami’s unique hybrid docu-drama film style. This can also be seen in what critics believed to be Kiarostami hallmark film, Taste of Cherry, which won the Palme d’Or in 1997.

Read More: Kung Fu Panda: The Illusion of Control

Taste of Cherry is made up largely of the main protagonist’s body driving in search of someone to bury him. The bulk of the film is made up of scenes shot in or around bodies range rover. Again, the cinematography is uncomplicated made up of mostly static long takes but it is Kiarostami’s composition of the image that makes this method work time and again giving us the best view of rural Iran. Like Close-Up and The Wind Will Carry Us, the editing of Taste of Cherry is typically Kiarostami-an. Kiarostami often edits his own films and in Taste of Cherry, he adopts the same slow-paced editing seen in most of his films. It is his conscious refrain from the fast-paced editing of conventional cinema as he explains that his films reflect his life’s pace and rhythm, however, Kiarostami, adhere to the style of continuity editing, employing the shot-reverse-shot technique in many of his films and complying with the 180-degree rule.

To achieve such depth with such simple techniques is what makes Abbas Kiarostami a truly remarkable filmmaker. While many film directors opt to execute elaborate storylines with boring techniques, it is Kiarostami’s humanistic cinema that reminds us that stories can be told in a sincere and honest manner and still inspire. Above all, it is his determination to be a filmmaker under such adverse conditions in Iran that should be a lesson to all who aspire likewise.

Last modified: September 23, 2021

[…] Read More: The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami: A Deep Dive Into His Movies […]

[…] Worth Reading: The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami: A Deep Dive Into His Movies […]

[…] Exclusively: The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami: A Deep Dive Into His Movies […]