“Perspective centers everything on the eyes of the beholder. It’s like a beam from a lighthouse, only instead of light traveling outwards, appearances travel in. Our tradition of the art calls those appearances reality. Perspective makes the eye the center of the visible world.”-John Berger

For over fifty years, Berger and his fellow art scholars have questioned the significance of the term ‘The Gaze’. What can ‘the gaze’ do? Who is being ‘gazed’ upon? Who does the ‘gazing’?

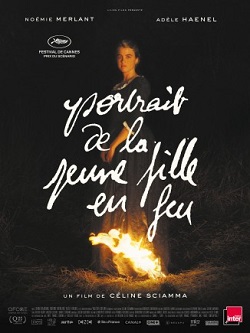

These same questions are asked today in Celine Sciamma’s 2019 film Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Pushing the boundaries of French filmmaking and queer representation, this film patiently observes the unfolding of a forbidden romance between a painter, Marianne, and her aristocratic subject, Heloise. Set against the minimalistic backdrop of a cold Britannic Island at the end of the eighteenth century, this love affair is told to us almost entirely through sensuous gestures and wistful glances. In addition to being a love story, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a careful meditation on the relationship between a painter and subject but more importantly, it’s a meditation on the power of the gaze. How it can simultaneously oppress us, liberate us, and allow us to transcend time and space.

While the gaze is often used interchangeably with a look or a glance in everyday life, its definition has expanded into a wide range of academic fields including but not limited to: psychoanalysis, art history, gender studies, and philosophy. For French philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, the gaze always objectifies. Meaning we are made aware of ourselves as subjects through the gaze of others, at which point we become painfully aware of ourselves as an object. In Sartre’s terms, the gaze is a consciousness of being looked at. In this sense, it’s an aggressive force that has the potential to subjugate us. It’s not about the eyes themselves, but rather about a battle of objectifying looks. Sartre’s negative feelings towards the gaze are demonstrated in the first act of Portrait of a Lady on Fire with the character of Heloise. When we first meet Heloise, it’s clear that her unstable sense of self is dictated by how she’s viewed by her aristocratic society. Before the story begins, it’s told that Heloise is a difficult subject because she refuses to pose for a painting. This battle between Heloise and the people who attempt to paint her encapsulates her resistance to being rendered as an object. Heloise’s refusal to be looked upon at the beginning of the film is an effort to fly beneath the gaze of others, and a rejection of the life she was born into. The portrait Marianne has been commissioned to paint can be viewed as a representation of Heloise’s subjugation to the gaze—the subjugation of being looked at and scrutinized by a potential suitor.

Now, let’s take a quick step back and look at the artist who was commissioned to paint all of the work seen in the film, Helene Delmaire. What I’ve noticed is that Delmaire seems to share a similar vision of the gaze to Sartre. Her portraits often feature women whose eyes, often regarded as the windows of the soul, have been shrouded or smudged out. This, like the smudged and distorted paintings in the film, is a visual rejection of the objectifying gaze.

The theory of the gaze in academia has come to resemble something of a powerful relation between the spectator and the subject, with terms like the male gaze, medical gaze, and post-colonial gaze. Critical theorist, Michel Foucault also views the gaze as an asymmetrical act of looking which is exemplified for him in the unequal power dynamic between doctor and patient and in the surveillance apparatus found in prisons and schools. But, there’s a peculiar moment in his writing in which he finds an exception to his rule. While looking at the 17th-century painting, Las Meninas by Diego Velazquez, Foucault notes that his work confuses our previous ideas about the gaze.

Las Meninas depicts life in the Spanish court. Featuring the little princess Margareta Teresa in the middle, with Velazquez himself to her left, and the rest of the court to her right. When a painting is actually a mirror reflecting the king and queen as they observe their subjects. And when we turn our attention to Velazquez, we notice that he’s, in fact, working on a painting. For Foucault, this glance, this exchange we have with the painter turns us as spectators into the object of his gaze. What this signals to Foucault is that the relationship between the viewer and the viewed is fundamentally different here.

This painting essentially does three things. One, it asks us to gaze at the subjects. Two, we are then gazed back at by the painter in the painting, and three, we assume the role of a viewer within the world of the painting itself. The painting is so puzzling to Foucault because it blurs the line between subject and object. Who is being gazed upon here? When we get in Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a very similar dynamic where the gaze between Marianne and Heloise is neutral and shared. When we meet Heloise, she’s gone through life being the object of the gaze, robbed of her agency, and is closed off and distant as a result. But once she meets Marianne, this changes. Marianne, rather than looking at Heloise, truly sees her.

In the long hours of studying and observing Heloise, Marianne takes the time to glimpse into her life, to begin to understand the underlying meanings behind her gestures and looks. On the other side, in the long hours that Heloise poses for Marianne, she gazes back at the painter and is able to do the same. Heloise sees freedom and agency in Marianne, and Marianne sees anger and fire in Heloise. And this provides a beautiful foundation on which their love can grow—a love that sees eye-to-eye.

The film takes place in two periods of time: the first being when the love story takes place and the second being years later as Marianne reflects on this relationship to her students. This split time frame allows for a compelling meditation on the power of memory and the images that linger in our minds. Much like a portrait, the gaze can capture the essence of a person that extends beyond their physical being. For the fleeting and forbidden time they spend together, Marianne and Heloise sensuously memorize each other’s features and habits before they lose sight of one another forever. Throughout the film, Marianne is haunted by a vision of Heloise in a wedding dress. But each time she turns around to confront this vision—it vanishes before her eyes.

This fleeting look is analogized in the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which Eloise reads to Marianne and their maid Sophia. As the Greek legend has it, Orpheus, son of Apollo, falls in love with a beautiful woman named Eurydice. The two marry for a brief time until Eurydice is suddenly killed by a snake while dancing in the forest with nymphs. Orpheus, struck with grief, makes a deal with Hades that he can bring Eurydice back to life on the condition that he does not look back at her as they leave the underworld. Orpheus is at first confident in his ability to be patient but grows suspicious when he’s unable to hear her footsteps. At the final moment, Orpheus loses faith and turns around to check on Eurydice, who’s then tragically pulled back into the underworld for all of eternity.

In their final moment together Heloise calls upon Marianne to turn around and look at her before she leaves the island. As Marianne turns around to look, she sees Heloise standing before her in a wedding dress—the vision that has been haunting her for all this time. Sciamma says she wanted Marianne to be tormented by her final moment with Heloise to signify the importance we place on firsts and lasts on the relationship. But what this also represents is the endurance of vision. For the majority of the film, Marianne’s gaze upon Heloise is produced almost entirely through memory. In the long hours, she spends struggling to recall a subject who isn’t there, and in the years she spends reminiscing on their love affair. In this instance, the gaze is not simply about seeing with the eyes.

When Orpheus and Marianne turn around to lock eyes with their lovers, the lover disappears. But in contrast to the physical nature of sight, one can gaze back into the mind to recall the subject of their desire through memory.

In a way, Portrait of a Lady on Fire shows us how true love, the willingness to gaze upon someone, to truly see them and to accept the same in return, can withstand the test of time. This film is a portrait of romance between two women in a time when this type of love was unacceptable, but it’s also in the words of Sciamma, a portrait of a woman at work. A look at how art is a labor of love, a timeless act that can be gazed upon for all of eternity.

Last modified: September 23, 2021

[…] Don’t Miss: Portrait of a Lady on Fire: What It Means To Truly See […]

[…] Interesting: Portrait of a Lady on Fire: What It Means To Truly See […]

[…] Don’t Miss: Portrait of a Lady on Fire: What It Means To Truly See […]